The Third Dimension of Corporate Strategy

In Chapter 8, we looked at the first two dimensions of corporate strategy: managing the degree of vertical integration and deciding which products and services to offer (the degree of diversification).

Now we turn to the third dimension: competing effectively around the world.

The Global Paradox

"If Strategy is about winning, and Walmart is 12x larger than IKEA, why do we consider IKEA the global winner?"

Walmart

The Financial GiantIKEA

The Global WinnerLesson: Global Strategy is not about how much you sell, but how well you cross borders.

The Flat-Pack Giant's Journey

From a small Swedish firm to a global standardization powerhouse.

The Swedish Paradox

It is somewhat surprising that the world’s most profitable retailer is a privately held furniture maker from Sweden and not a behemoth such as the U.S.-based Walmart. IKEA’s success in its international markets is critical to its competitive advantage.

Yet, IKEA took time (20 years) to perfect its core competencies before venturing beyond its home country. Today, IKEA succeeds in both rich developed countries, such as the United States and Germany, and emerging economies, such as China and India. Hailing from a small country in Northern Europe, IKEA earns the vast majority of its revenues outside of its borders. Moreover, IKEA’s fastest growth is outside Europe.

1. Political Risk: The Russia Exit (2022)

To protest the invasion of Ukraine, IKEA closed all 17 Russian stores. While Russia was only 4% of sales, it was a top supplier of wood (a critical input).

Insight: You can't just sell anywhere; your global supply chain binds you to geopolitics.

2. Reinventing for the City

70% of the world will live in cities by 2050. IKEA is pivoting from massive suburban stores to small city-center formats (London, Paris, Mumbai) and acquiring TaskRabbit to solve the customer pain point of assembly.

Sales by Region (2024)

Europe is the fortress (71%), but future growth relies on Asia & Americas.

What is Globalization?

It is not just selling abroad. It is the process of closer integration and exchange between different countries and peoples, driven by falling trade barriers and better telecommunications.

MNE (Multinational Enterprise)

A firm that deploys resources in at least two countries.

Examples: Boeing, Infosys, Samsung.

FDI (Foreign Direct Investment)

Investing in value chain activities abroad.

Invested $1B to be closer to customers (Delta) and avoid tariffs.

Stages of Globalization

1.0 (1900-1941): Sales/Operations. (Slow)

2.0 (1945-2000): MNEs replicate home model. (Scale)

3.0 (21st Century): Seamless global networks. (Integrated)

The $85 Trillion World Economy

Globalization of Talent

6 million students study abroad annually.

Why Go Global? Three Strategic Drivers

1. Access Markets

US market saturated. Future growth is 100% international.

Expanded to UK, Australia, NZ to find growth beyond India.

2. Low-Cost Inputs

Powerhouse for decades. Now shifting to "Designed in China 2025" (AI, Robotics) as wages rise.

Infosys, TCS, Wipro. Built on English-speaking talent + cost arbitrage. US giants (IBM, Google) invest heavily in Bangalore.

3. New Competencies

- AstraZeneca: Moved to Boston (Biotech).

- Unilever: Shanghai (Consumer insights).

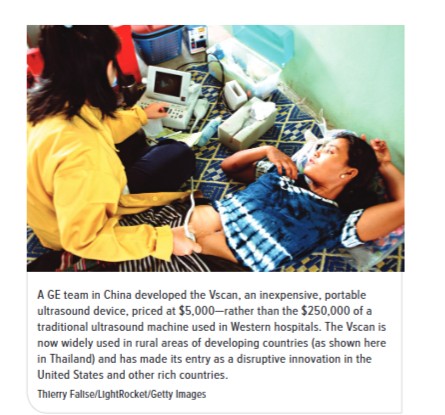

GE Healthcare (India): Created the $800 MAC 400 ECG in Bangalore (vs $2000 US models). A "Reverse Innovation" now sold globally.

The Shift to Globalization 3.0: Many MNEs are now replacing the one-way innovation flow from Western economies to developing markets with a polycentric innovation strategy—drawing on multiple, equally important innovation hubs throughout the world.

GE Global Research orchestrates a "network of excellence" with hubs in NY, Bangalore, Shanghai, and Munich. Emerging economies are becoming hotbeds for low-cost innovations like the MAC 400 (India) and Vscan (China) that disrupt developed markets.

The Liability of Foreignness

Expanding is dangerous. You don't know the culture, rules, or customers.

Stranger in a Strange Land

Disaster. Germans found "smiling greeters" creepy and hated having groceries bagged. Walmart lost billions.

Failed initially. Indians eat savory breakfasts (Idli, Dosa), not sweet donuts. Had to pivot to burgers.

Where to Compete?

Distance is Not Just Miles (CAGE Framework)

Cultural

Values, Religion, Language

Ex: Beef in India

McDonald's had to reinvent menu (Maharaja Mac).

Administrative

Laws, Currency, Politics

Ex: Eurozone

Low distance within EU. High distance for US-China.

Geographic

Physical, Climate, Time

Ex: Himalayas

India & China are neighbors, but trade is hard.

Economic

Income, Infrastructure

Ex: Luxury vs Value

Mercedes in Germany vs. Maruti in India.

Cultural Distance

Gillette's Sharp Lesson in India

The Failure: Vector (2002)

In 2002, P&G launched the Vector razor in India. Research showed Indian men had thicker hair, so they added a plastic unclogging bar. It flopped. Why? The research was done with Indian students at MIT, not in India. A crucial insight was missed: most Indian men don't have running water. They shave using a cup of water. Without running water to rinse it, the "unclogging" bar clogged the razor instantly.

The Success: Gillette Guard

Learning from the face-palm moment, Gillette sent 20 people to India to spend 3,000 hours with 1,000 consumers in their homes. The result was the Gillette Guard. It had a single blade (for safety, not just closeness), an easy-rinse design for cup shaving, and a low cost. It became a bestseller.

Admin/Political Distance

The Vodafone Tax Saga

The Context (2007)

Vodafone acquired a 67% stake in Hutchison Essar, a major Indian telecom player. The deal took place offshore in the Cayman Islands between two foreign entities.

The Regulatory Shock (2012)

India's tax department demanded $2.2 billion in capital gains tax. When the Supreme Court ruled in Vodafone's favor, the government passed a retrospective tax law to override the court ruling and claim the money anyway.

The Impact

This move highlighted significant Administrative Distance risk. The unpredictability of India's regulatory environment spooked foreign investors, showing that legal institutions were not always independent of political will. (Note: The tax was finally scrapped in 2021).

Key Takeaway: Administrative distance includes legal stability. Unpredictable regulations act as a massive barrier to foreign investment.

Geographic Distance

Amul's Fresh Milk Challenge

The Context

Geographic distance isn't just miles; it's logistics, time zones, and climate. For Amul Dairy, exporting shelf-stable products to the U.S. was easy. But fresh milk? That's a different beast.

The Hurdle: Perishability

The extreme physical distance between India and the U.S. makes exporting fresh milk, buttermilk, and paneer logistically impossible. Maintaining an unbroken cold chain across thousands of miles adds massive costs, destroying margins in a competitive market.

The Solution (2024)

Amul didn't ship milk; they shipped the recipe. They partnered with the Michigan Milk Producers Association to process milk locally in the U.S. using Amul's standards.

Key Takeaway: When geographic distance makes trade impossible (e.g., perishables), switch from "Exporting" to "Strategic Alliance" (local production).

Geographic Failure

Rural Logistics (PepperTap/Doodhwala)

The Failures: PepperTap & Doodhwala

Startups like PepperTap and Doodhwala aimed to revolutionize grocery delivery in India. They failed largely because they underestimated the Geographic Distance within India itself.

The Hurdle: Last-Mile Connectivity

In suburban and rural India, lack of standardized addresses and poor road infrastructure made last-mile delivery highly inefficient and costly. Drivers spent too much time locating customers.

Infrastructure Woes

Bad roads and traffic congestion increased delivery times and vehicle maintenance costs. A lack of quality local warehousing meant inventory had to travel further, making the business model unsustainable for low-margin, high-volume products outside major cities.

Key Takeaway: Geographic distance includes internal infrastructure. Scaling logistics models from urban to rural settings fails if infrastructure doesn't support low-margin, high-volume delivery.

Administrative Distance

Regulatory & Institutional Mismatches

Karuturi Global (Ethiopia)

Leased 100k hectares in Ethiopia. Failed due to shifting regulations, land disputes with indigenous communities, and the government cancelling the lease. Highlighted the risk of weak property rights institutions.

Satyam Scandal (Internal)

Massive accounting fraud ($1B+). While internal, it damaged "Brand India" globally, increasing the perceived administrative distance (trust/governance risk) for foreign investors.

Home Depot (China)

Failed because the Chinese government focuses on large construction, and labor is cheap. Chinese consumers don't "Do-It-Yourself" (DIY); they hire cheap labor ("Do-It-For-Me"). Administrative and economic mismatch.

Google (China)

Exited due to direct conflict with government censorship laws. A purely political/administrative incompatibility.

Economic Distance

Income & Aspirations

Tata Nano ("The Cheap Car")

Marketed as the "world's cheapest car" to target low-income families upgrading from scooters.

The Mistake: Marketing created an economic perception gap. In India, a car is a status symbol. Nobody wanted to be seen driving the "cheapest" car. It failed because it ignored the aspirational aspect of economic distance.

Strategies for Entering Foreign Markets

Assuming an MNE has decided why and where to enter a foreign market, the critical remaining decision is how to do so.

The Investment & Control Continuum

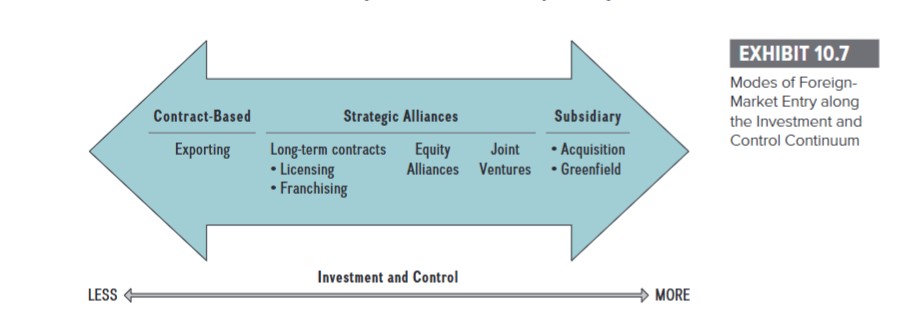

HOW DO MNEs ENTER FOREIGN MARKETS?

Assuming an MNE has decided why and where to enter a foreign market, the remaining decision is how to do so. The chart above displays the different options managers have when entering foreign markets, along with the required investments necessary and the control they can exert.

On the left end of the continuum are vehicles of foreign expansion that require low investments but allow for only a low level of control. On the right are foreign-entry modes that require a high level of investments in terms of capital and other resources, but afford a high level of control. Foreign-entry modes with a high level of control such as foreign acquisitions reduce the firm’s exposure to two particular downsides of global business: loss of reputation and loss of intellectual property.

Exporting—producing goods in one country to sell in another—is one of the oldest forms of internationalization (part of Globalization 1.0). It is often used to test whether a foreign market is ready for a firm’s products. When studying vertical integration and diversification (in Chapter 8), we discussed in detail different forms along the make-or-buy continuum. As discussed in Chapter 9, strategic alliances (including licensing, franchising, and joint ventures) and acquisitions are popular vehicles for entry into foreign markets. Because we discussed these organizational arrangements in detail in previous chapters, we keep this section on foreign-entry modes brief.

The framework illustrated above, moving from left to right, has been suggested as a stage model of sequential commitment to a foreign market over time. Though it does not apply to globally born companies such as internet companies, it is relevant for manufacturing companies that are just now expanding into global operations. In some instances, the host country requires foreign companies to form joint ventures in order to conduct business there, but some MNEs prefer greenfield operations—building new, fully owned plants and facilities from scratch.

Case Example: Manufacturing Entry

Motorola received permission to build a fully owned plant in China when it entered (in the 1990s), as did Tesla when it built its Giga factory in Shanghai, with the first cars (Models 3/Y) rolling off the assembly line in 2020. Tesla cars built in China are for the domestic market and for export to European markets. Estimates indicate that Tesla’s production cost per car is about 30% lower in China than in the United States, with no quality differences.

LO 10-4: Compare and contrast the different options MNEs have for entering foreign markets.

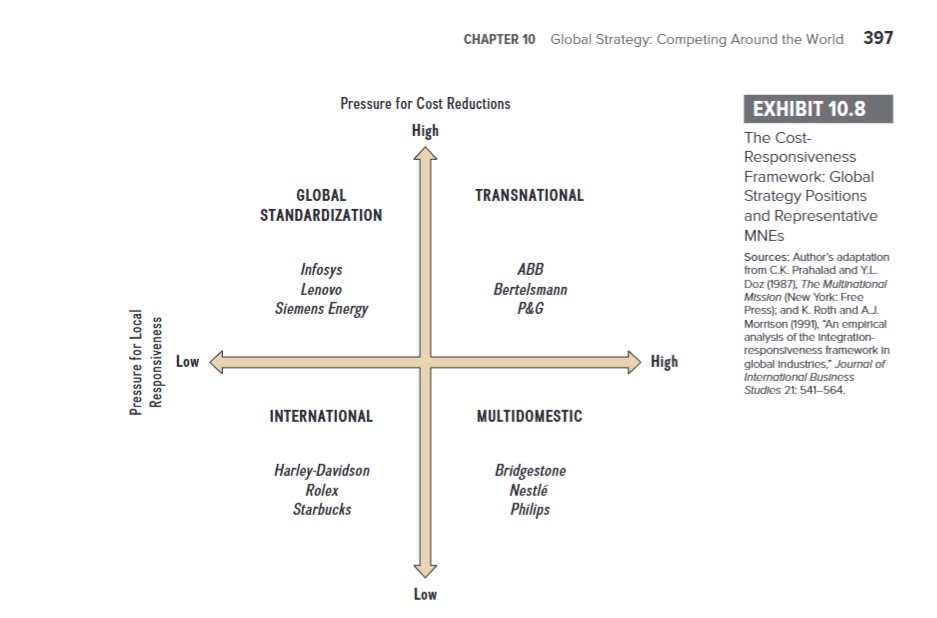

How to Compete?

MNEs face two opposing forces when competing globally: Cost Reduction versus Local Responsiveness. The "Globalization Hypothesis" suggests consumer needs are converging (e.g., iPhones are desired everywhere), favoring cost reduction. However, national differences (culture, infrastructure) persist, requiring local adaptation.

Strategies of Global Competition

Integration-Responsiveness Framework (Exhibit 10.9)

| Strategy | Characteristics | Benefits & Risks | Global Giants | Indian Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

International

Low Pressure for Cost Low Pressure for Local |

Leverage home-based core competencies. Sell the same product/service globally. Often the first step (Exporting). |

|

Rolex Sells Swiss luxury/heritage worldwide without adaptation. |

Royal Enfield Sells the "Himalayan" rugged experience globally based on Indian heritage. |

|

Multidomestic

Low Pressure for Cost High Pressure for Local |

Maximize local responsiveness. Consumers perceive company as "local". Duplication of key functions across countries. |

|

Nestlé Customizes food products and flavors for every specific country market. |

Godrej Consumer Tailors products like hair color and insecticides specifically for African/Indonesian needs. |

|

Global-Standardization

High Pressure for Cost Low Pressure for Local |

Economies of scale and location economies. Global division of labor. Products are standardized commodities. |

|

Lenovo Sells standardized computer hardware globally from efficient manufacturing hubs. |

Infosys / TCS Delivers standardized IT services and BPO solutions via a Global Delivery Model. |

|

Transnational

High Pressure for Cost High Pressure for Local |

"Think Globally, Act Locally." Combines high differentiation with low cost (Blue Ocean). Uses a global matrix structure. Hardest to implement. |

|

Unilever Attempts to standardize back-end operations while keeping front-end brands local. |

Tata Motors Integrates Jaguar Land Rover (Luxury/Global) technology with Indian operations (Local/Cost). |

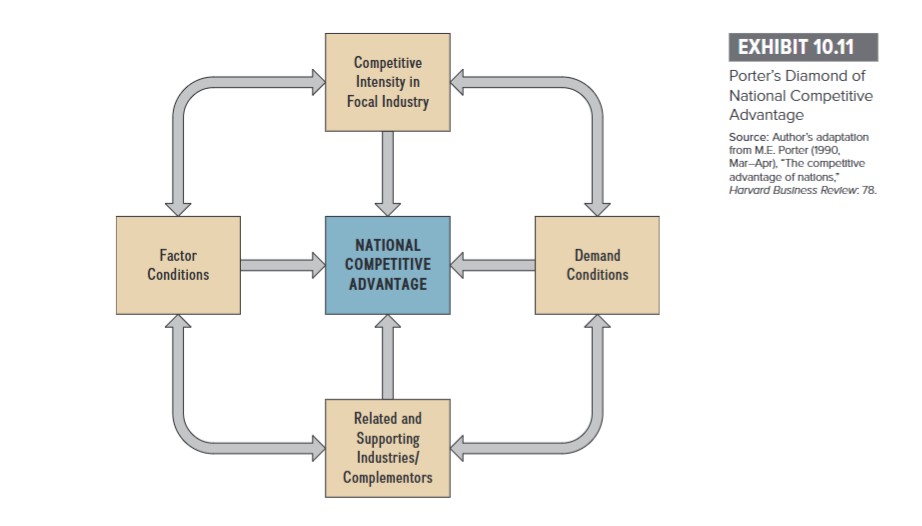

National Competitive Advantage

Why do some nations lead? Porter's Diamond Framework.

Natural resources (oil, minerals) are often not needed to generate world-leading companies. In fact, many resource-rich countries (e.g., Venezuela, Iran) are not home to leading global firms. In contrast, countries that lack natural resources (e.g., Japan, Singapore, Switzerland) often develop world-class human capital to compensate.

Michael Porter advanced a framework to explain National Competitive Advantage—why some nations outperform others in specific industries. It consists of four interrelated factors known as Porter's Diamond.

1. Factor Conditions

"Constraint breeds creativity."

A nation's position in factors of production, such as skilled labor or infrastructure, necessary to compete in a given industry. Paradoxically, disadvantages in basic factors (like a lack of raw materials) can create pressures to invest in advanced factors (like specialized research).

Silicon Valley (USA): Proximity to Stanford University created a density of specialized engineering talent, fueling the tech boom.

Infosys / TCS: Leveraged India's abundance of English-speaking engineering graduates (human capital) to overcome infrastructure gaps.

2. Demand Conditions

"Tough customers create great firms."

The nature of home-market demand. Sophisticated and demanding local customers push firms to innovate and improve quality. For example, dense urban living in Japan led customers to demand quiet, small, energy-efficient air conditioners.

Nokia (Finland): Remote, sparse populations demanded reliable mobile comms for survival, pushing Nokia to early leadership.

Paytm / UPI: A lack of POS terminals + demonetization created a huge demand for digital payments, driving the world's most advanced real-time payment system.

3. Competitive Intensity

"Diamonds are forged under pressure."

Companies that face a highly competitive environment at home tend to outperform global competitors. Fierce domestic rivalry forces firms to become efficient and innovative.

German Auto (BMW vs Mercedes): Intense rivalry + Autobahn (no speed limits) forces superior engineering performance.

Telecom (Jio vs Airtel): Brutal price wars created the world's cheapest mobile data, forcing extreme operational efficiency.

4. Related & Supporting Industries

"Success attracts success."

The presence of supplier industries and related industries that are internationally competitive. These clusters allow for fast knowledge sharing and innovation spillover.

Toyota (Japan): A network of world-class suppliers enabled lean manufacturing and fast two-way knowledge sharing.

Chennai Auto Cluster: Known as the "Detroit of India," a dense network of component makers (TVS, Amalgamations) supports Hyundai, BMW, and Ford factories.

The Strategist's Summary

Global strategy is a balancing act. You must navigate the CAGE Distance, choose the right Entry Mode to protect your IP, and balance Cost vs. Localization.

Global Domination: The CEO Challenge

Take the helm of TechNova. Navigate 5 critical strategic crossroads. Feedback is delayed until the end. Only the best strategists survive.

Mission Briefing

TechNova dominates the US market. Shareholders demand global growth. You must expand internationally without destroying the company.

Scenario Title

Scenario description...

Test Your Knowledge

Have you mastered the concepts of Build-Borrow-Buy, Alliances, and M&A? Complete these 15 questions to certify your understanding.